Rescue Below Tahquitz Peak

|

April 1-2, 2012 |

Written by Helene Lohr

5:47 p.m. I had just gotten down from a 7-mile trail run when the call-out came. The text message was brief: “We have a rescue, snow and ice. Call the rescue line.” I jumped up off the couch, pressing the phone to my ear and beelining it towards my gear closet. The message on the rescue line from Gwenda says we have a 17-year-old boy stuck up in the Chinquapin Bowl area below Tahquitz peak; that he’s uninjured, but not able to safely move from his position; and that he managed to get a call out to 911 despite the sketchy cell signal in that area. I get a shiver down my spine. The bowl is an extremely steep drop off on the northeast face of the peak- this time of year it’ll be covered in a nasty sheet of ice. I state my availability after the beep: “This is Helene. I’ll be there in 30.”

I sift through my gear closet, adding items to my basic grab-n-go pack: ice axe, crampons, gaiters, a heavy down jacket, and my warmest sleeping bag in case we need to bivy overnight. It had been a warm day down in town - almost 60 degrees - but the sun is already setting. It’ll be a different story up in the high country. I add an extra jacket, three headlamps with extra batteries, a pair of micro-spikes, extra food and water just in case. You never know exactly what conditions you’ll be getting into, and it’s usually a safe bet that the subject won’t have been prepared for this sort of worst-case scenario.

I swing on my winter pack and head out the door. Mission Base (base operations) is at the Humber Park parking lot at the foot of Tahquitz Rock. Looking up far above I can see the sheer slope that we’ll be traversing to reach the subject. This would be a lot faster and easier if we could be air-dropped in the high country, but the only copter currently available is CHP and they don’t fly at night. That means we’ll just have to hoof it. It’ll take us a few hours in these conditions to make it up there. Hopefully the subject doesn’t get brave in the meantime and try to move.

Lee Arnson, Les Walker, and I are the first on scene. More rescuers are en route - we can always use the people. Paul Caraher is bringing the team truck up from Hemet with all the gear that may be needed if this rescue escalates. We form our plan of attack. Les will stay on scene and run Base until Paul gets here to take over. Lee and I will head up Devil’s Slide, while other rescuers will be shunted up the trail behind us as needed, or else towards the South Ridge Trail in case the subject manages to cross the ice field and head down. Lee and I swing on the full weight of our winter packs and start up the trail. A few minutes later Will Carlson lopes up the trail behind us. After a warm welcome we’re off again at a quick clip.

The conditions don’t really get challenging until we reach the saddle [Saddle Junction]. As we come into the junction the wind kicks increasingly strong gusts our way. What has been patchy snow coverage turns into a continuous sheet of ice and hardened snow. If the subject is stuck long in this sort of wind on a fully exposed slope he runs a high risk of hypothermia. Getting him out will be difficult enough without this added complication. I glance at my thermometer - it’s already down to 18 degrees… and with the wind chill…

We bear a sharp right up the PCT towards Chinquapin with a renewed fervor. We cut cross-country across the slopes above the buried trail to save time. The snow is really just crunchy ice from continuous freeze/melt cycles. We walk on top of the sheet of ice, not sinking in at all. We’re essentially walking on a slanted skating rink, in the dark, and on a windy night. I swing my ice axe off my pack and into my uphill hand where it can do some good. Our crampon spikes bite into the edge of the mountain and keep us from sliding. The slope here ranges from only 20 to 35 degrees but it’s already taking concentration to place each step correctly.

About two hours in we reach the first overlook into the bowl. The wind comes up howling over the lip and buffets us. We wait for our chance - when it dies down we yell out over the edge “Hello! … Hello!” No answer. We shout again, and again. No answer. Will said: “He should have heard that if he’s out there.” Lee gives me a raised eyebrow and I answer with my own worried look. “Maybe he made it out the South Ridge Side,” I say with a doubtful tone. We duck back to the other side of the ridge lip and continue our trek to the far side of the bowl. Reaching the flat area around the saddle above the bowl we stop and look for tracks. Bingo! Fresh snowshoe tracks are heading off alone across the snow. “Base, Team one…” Lee gets radio confirmation from base that the subject had MSR snowshoes. We follow the tracks across an increasingly steep slope, alternately yelling the subject’s name. After about 20 minutes Will gets voice contact and we carefully make our way towards the sound. Along the way we gather up a pair of trekking poles caught splayed out in the tips of some brush. “This must be where he slipped.”

The slope has increased to about 45 degrees, some particularly nasty sections even ranging towards 60 degrees. I take extreme care with every step, making sure to plant my axe securely before I move each foot forward. Even with the weight of the winter pack I don’t have enough mass to really bite into the ice, so I have to put extra downward punch in every step to make sure it’s secure. I’m definitely feeling my trail run earlier in the day. Maybe I shouldn’t have pushed it so hard. Lee and Will pick their ways over 100 feet downslope to the subject. He is lodged in the well of the tree that stopped his slide and saved his life. They check his status- amazingly he’s uninjured and is still awake and alert, but very cold. They outfit him with a down jacket, crampons, my extra headlamp, and one of our back-up harnesses, while I wait above securing the belay we’ve rigged. I notice that the tree I’m nestled against is encased in an inch thick sheet of ice. The thermometer reads 13 degrees, the wind chill bringing it down below 0. In a matter of minutes Lee and Will tie the subject in to the line and get him moving upslope as I take out slack.

Belay station anchored to ice covered tree

Photo by Helene Lohr

We radio in to let Base know we have the subject and that he’s in good condition. Due to the conditions the call is made to not crowd the slope with too many rescuers. We have enough people to set up and run belay and monitor the subject’s wellbeing. Pete Carlson and Alan Lovegreen (Team Two) have hiked up to the saddle behind us. Carlos Carter and Les Walker (Team Three) are approaching on the South Ridge Trail. Base calls them all back. Despite their cool heads and experience, on this steep windy slope more rescuers would not necessarily be better.

The wind is increasing, with sudden howling gusts interrupted by unpredictable bouts of silence making it even more difficult to keep our footing. One very strong and abrupt gust actually lifts me up and knocks me off my feet. I feel a rush of adrenaline as my training kicks in and I managed to arrest my fall before it even starts. I stare down the slope and imagine sliding uncontrollably down the several thousand feet to the bottom of the bowl.

The decision is made to head up towards the ridgeline instead of traversing an increasingly steep slope in dangerous wind conditions. If we can get up there it’s a straight, if rocky, shot to the Forest Service Fire Lookout Tower. The only problem will be finding a way in. This time of year the Lookout is still locked down tighter than San Quentin.

On the third try I manage to make a cell call out to my friend Lookout Coordinator Bob Romano and get the combo to the tower. He wishes us safety and luck. I tell him that we appreciate the help - getting the subject (and us) warm and out of the wind will likely be critical to keeping us all safe.

We slowly coax the subject up the incline along a series of belays. He’s understandably scared and nervous after his experience, but we can’t afford to move too slowly. In these conditions succumbing to the cold is a looming risk for the whole team if we don’t keep moving and get out of the wind soon. I’m already shivering off and on and I can see that the guys are working through the cold as well. In order to set up the belays quickly they have to take their gloves off, instantly leaching the heat from their hands and putting them at greater risk the longer we spend on the slope.

We crest the edge of the Tahquitz ridge and the wind abruptly dies. Now that I’m reasonably sure of my own safety I turn my attention to checking more thoroughly on the subject’s wellbeing. He’s still shivering, but that’s a relatively good sign. It means that although he’s cold, his body still has enough energy to try and produce much needed heat. I engage him in conversation to both encourage him and make sure he is still alert.

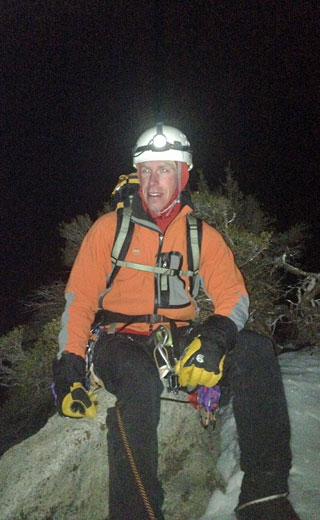

Rescuer Will Carlson on Tahquitz Ridge

Photo by Helene Lohr

He relates that, expecting only a day hike, he only brought a small daypack with minimal food and water. This sets off alarm bells in my head. In extreme conditions the body needs both the calories from food and enough water to adequately maintain body temperature. If a person is low on energy and dehydrated he runs a much higher risk of hypothermia. I break out my extra provisions and make sure he eats. Lee melts a Nalgene worth of snow and we watch him drink. After a few minutes he noticeably peps up.

Will has gone on ahead to explore our route along the ridgeline. He comes back with good news - only about a half an hour more to a flat section and then it’ll be the “simple” grind of making our way to the tower. The guys take over the subject and I head out to open up the tower and get it ready.

Rescuer Lee Arnson approaching Forest Service lookout tower

Photo by Helene Lohr

It’s about 4:00 in the morning when the whole group finally meets up at the tower. We give the subject the narrow bed and slide him into one of the extra sleeping bags. We all share a few snack bars and some water and settle down onto the floor for a couple hours rest. Being out of the wind and relatively warm is an amazing feeling after this long night. After a wake-up serenade from the radio at 6 a.m. (thanks Paul!) we pack up our gear and hit the trail. The wind had blessedly died down around dawn. The South Ridge trail, with its southern exposure, is refreshingly clear of snow and the going is easy. My legs are stiff from overuse and it takes a while to really get into a rhythm, but the siren song of scrambled eggs and bacon is calling us all and we make short work of it.

Pete Carlson and Les Walker are waiting on us at the trailhead - I can’t say I’ve ever been happier to see them - especially since they were there to drive us out. We brought the boy back to his grateful mother up at Base and then headed out to a much deserved breakfast.

Looking back over the night I know that the members of RMRU are the best. From working with Will and Lee in the worst conditions on the mountain, to the support from the backup teams (Carlos, Alan, Les and Pete) ready to spring into action, to the guidance and information from Paul at Base, I wouldn’t want any other team of mountaineers at my back.

RMRU team members present: Lee Arnson, Paul Caraher, Pete Carlson, William Carlson, Carlos Carter, Helene Lohr, Alan Lovegreen, and Les Walker.

Share this story: