Hoist Rescue

|

February 6, 2016 |

Written by Kevin Kearn

On Saturday after a long day of snow and ice rescue training above Idyllwild, the Riverside Sheriff’s Office (RSO) alerted RMRU to rescue three young males, ages 17-18, stranded above the city of San Jacinto. Glen directed Ray and myself to report to the RSO’s Aviation Detachment at Hemet-Ryan Airfield to attempt to conduct a hoist of the three-man group as the sun was starting to go down.

RSO had established communications with the party via cell phone and had a relatively accurate fix on their location just southwest of the “S” in the mountains above Hemet and San Jacinto. Temperatures were unseasonably warm in the 60’s in and although hypothermia was not a major concern, one of the three had reportedly injured his ankle, and the group was without water, food, or the ability to shelter for the night.

Ray and I arrived and reconfigured our packs to conduct a hoist. Having just come off of snow and ice that afternoon, we slimmed down our packs and loaded up ‘screamer suits’ to extract our subjects. We also brought medical equipment to possibly splint the ankle injury if required. Together with the pilot and Technical Flight Officer (TFO) we planned to drop me in first, followed by Ray. After evaluating the subjects and rendering any emergency care, we’d suit up the first two subjects, and then the TFO would hoist Ray back up. As I hooked the subjects up below, the TFO would hoist them and Ray would secure them inside the aircraft. I would remain with the third subject as they flew the other two down to the command post established by RSO Deputy Pingle on Soboba Rd below. Then they’d return and extract the third subject and myself.

After launching at 6pm, conditions changed as we approached the mountains. It was now dark and the Santa Ana winds that had brought the warm weather were now much more severe in the mountains. The subjects, who seemed fine, were on a knife edge spine that came off a steep ridge into a canyon with a high wall close to subjects. The spine itself was less than 6 feet wide with 20’+ drop offs on either side. The restrictive terrain amplified wind gusts which were already sustained at 30 knots.

Over our headsets, we acknowledged that this was extremely tricky. With the door open, hooked up, and my feet on the skid, I remembered the fact that more mountain rescue personnel are killed in aircraft incidents than on cliffs or accidents on the ground. Still Ray and I, having had solid training for years with this very crew, were supremely confident in their judgement and ability. We knew if anyone could lower us into a tiny target in high winds and “pin the tail on the donkey”, the Pilot and TFO could. Of course, there was also a risk that we might get stranded down there if the winds increased between hoists as well.

Ridge Top where Subjects got Stuck

Photo by Kevin Kearn.

After another gust of wind pushed our tiny helicopter precariously toward the wall again, our wise pilots decided to abort for now – it was just too dangerous. The TFO signaled abort and I climbed back inside. I’m sure our subjects were disheartened to see our aircraft depart - I could empathize. We descended and landed near the RSO command post off Soboba Rd. and talked to Deputy Pingle on the ground.

The weather forecast was for continued winds all night. We contacted Glen Henderson and let him know that we had to abort the hoist and that the position of the subjects would require a ground rescue that would probably demand some limited technical work given their position and the unknown mobility of the ankle-injured subject. Glen and Gwenda, still at the MRA conference in Salt Lake City, then put out the call for reinforcements from the rest of the team – already exhausted and probably asleep after intense training on snow and ice all day.

Deputy Pingle informed us that the subjects, who originally had three cellphones, now had only one still charged with only 30% battery left. We asked that he update the subjects and direct the them to conserve their remaining power by switching to airplane mode and only coming up at the top of the hour for ten minutes (or an emergency).

Since technical ground operations are significantly faster and easier if we can drop teams laden with extra equipment above the subjects to descend rather than climb to them, our pilots agreed to let us conduct a better aerial reconnaissance while our ground team and rescue truck assembled over the next two hours. In order to find a suitable Landing Zone (LZ) and identify a route to the subjects, the pilot suggested we go back and get Night Vision Goggles (NVGs) for the TFO and I since illumination was so poor. We flew back to Hemet-Ryan airfield. We got the goggles but while preparing a different aircraft, RSO got another call to assist the Idyllwild Fire Department. RSO now asked that Ray and I assist in rescuing a critically injured man whose car had gone off a cliff near Poppet Flats (see Mission 2016-003). We let the team know we’d been re-tasked.

We reloaded our original aircraft, swapped our screamer suits for a collapsible stokes litter, and launched to assist Idyllwild. When we arrived, firemen were nearly complete in hauling the victim up the steep slope with their own haul system. Although we landed briefly, it was clear that the victim’s serious head injuries precluded evacuation on the outside of RSO’s aircraft, and a special helicopter (Mercy Air) with paramedic onboard and capability to internally load the litter was on its way. We did observe that winds had died down significantly and took off to check winds near our original subjects’ location on the mountain.

Winds had dropped below 30 knots when we arrived at the point last seen on the knife edge, however our subjects had moved. Since they were surrounded by steep drop offs, it was more likely that they had mustered the courage to scramble up the class 4+ slope above them. Without locating their exact location and not wanting to waste time with the window of low winds, we returned to Hemet-Ryan Airfield again to swap out the litter and retrieve the screamer suits. The extraction plan remained the same if we could not actually land. I attempted to call Lee and update the RMRU ground team again before we launched.

As we returned, we stopped briefly near the command post to load the new coordinates Deputy Pingle had obtained for the subjects’ location. As predicted, they had ascended and were not far from the top. This was also good news in the that the reportedly ankle-injured subject was mobile. After flying to the top, we saw the subjects flashing their cellphone flashlight at us – approximately 300’ from the summit.

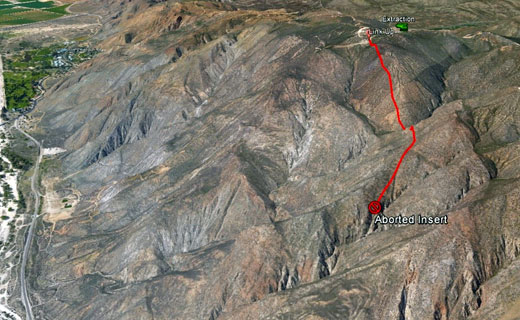

Map showing where things happened

Photo by Raymond Weden.

Radio antennas and obstacles made it difficult to find a place to safely land so we executed the hoist plan. After Ray and I were lowered, we ran to the subjects. All were somewhat dehydrated and one complained of an injured ankle. Ray did a quick check, gave him some water, and we got him up and moving towards to the extraction point.

There we quickly suited up the two eighteen-year olds – including the one with the twisted ankle. (The seventeen-year old asked that the other two go before him.) Ray went up first and I sent up the other two as planned. As we waited for the helicopter to return for us, I gave the remaining seventeen-year old a liter of water and food.

He explained how he had brought eight (8 Oz.) bottles of water to hike with his two friends. One of the two brought three Fiber-1 bars but no one else brought food, water, or supplies besides a pair of gloves and sweatshirts. No one had a map. Despite acknowledging that they were ill-prepared to go, they decided to hike anyway. They got disoriented and one eighteen-year old slipped down an embankment and twisted his ankle. While trying to descend, they run into a knife edge spine and couldn’t descend safely any further when they called 911. After our aircraft had circled above and left, the ankle-injured teen feared “he was going to die” and the seventeen-year old took charge of the two older boys and made them climb up the cliff – eventually getting them to location where we found them. When I asked, what he planned to do after high school, he responded,” I plan to join the Army. I plan to go Infantry.”

The helicopter returned, lowered a screamer suit to me, and he was hoisted into the aircraft before I followed him. We landed shortly thereafter at the command post where Deputy Pingle took charge of the three. While I re-packed the screamer suits at the aircraft, Deputy Pingle took a picture of our hikers in good health and spirits with Ray.

Hikers at Base, Raymond on the right

Photo by Deputy Pingle.

The rest of RMRU’s ground team, having fully assembled now with seven additional personnel, all of whom had trained hard all day in the snow, was relieved that it didn’t have to continue the mission and buoyed by the success of this rescue before midnight. This ended the second mission in a row that happened after a long day(s) of team training. The fact that nine exhausted, volunteer rescuers returned again for what could have been another physically demanding night mission, underscores the character, commitment, and reliability of RMRU team members.

Lessons Learned:

Don’t Rush to Failure: All too often, we unwisely make poor decisions because we don’t thoroughly examine and manage risk – identification of all hazards, likelihood of occurrence, and severity of consequences. The three young men recognized that they lacked food, water, a map (other than on cellphone), and the proper gear to hike in the mountains but didn’t fully think through what could possibly go wrong and what the impact might be – getting lost, injured, trapped overnight. Similarly, the pilots and members of RMRU, chose to abort the first insertion attempt after determining that the situation on the ground didn’t require excessive risk with the potentially catastrophic consequences. The RMRU ground team also chose wisely to pause as the winds died down rather than rush up into the mountains and steep terrain while the subjects moved away from them. We must guard are desire to move out immediately when it may only be to make ourselves feel like we’re doing something, and premature commitment to a course of action may with limited resources may actually jeopardize the flexibility, mission, and even lives. Bottom line: We must be skillful and always think before we act.

Cultivate Physical and Mental Toughness: Both in yourself and your organization, it is important to be physically and mentally tough. The one 18-year old who claimed he had an injury, was in fact, in far better condition than he believed himself to be …and quite still capable of walking. It was clear that he had given up, largely in his mind when he became lost and twisted his ankle a little. At one point, he had resigned himself that he would die, didn’t want to move, and demoralized and burdened his friends. It was only when the youngest boy took charge and led the other two, that their situation turned around. Similarly, RMRU members who were exhausted and trained all day in the mountains (some up for nearly 20 hours already) still summoned the strength to come out to support the rescue and were ready to hike/climb all night if required. Maintaining physical fitness not only gives one capability to be strong when required, but also makes a person less prone to injury and gives one the personal confidence that they can persevere in the wilderness.

RMRU Members Involved: Lee Arnson, Cameron Dickinson, Michael George, Glenn Henderson, Kevin Kearn, Rob May, Dana Potts, Wayne Smith, and Raymond Weden.

Sheriff's Aviation: Mike Calhoun (Pilot), Eric Bashta (TFO).